Are you trying to edit Sudoers File in Linux?

This guide can help you.

The sudoers file is located in "/etc/sudoers".

Here at Ibmi Media, as part of our Server Management Services, we regularly help our Customers to perform Linux related Installation and Tasks.

In this context, we will look into how to securely obtain root privileges.

How to Edit Sudoers File in Linux ?

A special user, called root, has super-user privileges. This is an administrative account without the restrictions that are present on normal users.

Users can execute commands with super-user or root privileges in a number of different ways.

In this article, we will discuss how to correctly and securely obtain root privileges, with a special focus on editing the /etc/sudoers file.

In order to see how to edit Sudoers File in Linux, as a first step, we will use an Ubuntu 20.04 server. However, most modern Linux distributions such as Debian and CentOS should operate in a similar manner.

How To Obtain Root Privileges in Linux?

There are three basic ways to obtain root privileges, which vary in their level of sophistication.

1. Log In As Root

The simplest and most straightforward method of obtaining root privileges is to directly log into the server as the root user.

If we login into a local machine, we enter root as the username at the login prompt and enter the root password.

If we login through SSH, we specify the root user prior to the IP address or domain name in the SSH connection string:

$ ssh root@server_domain_or_ipLikewise, if we have not set up SSH keys for the root user, we enter the root password when prompted.

2. How to Use su to Become Root ?

It is not recommended to directly login as root. Because, it is easy to begin using the system for non-administrative tasks, which is dangerous.

The next way is to gain super-user privileges and to become the root user at any time. We can do this by invoking the su command, which stands for “substitute user”.

To gain root privileges, type:

$ suEnter the root user’s password, and we will be dropped into a root shell session.

Once we finish the tasks which require root privileges, return to the normal shell by typing:

# exit3. How to Use sudo to Execute Commands as Root ?

Another way to obtain root privileges is with the sudo command.

The sudo command allows us to execute one-off commands with root privileges, without the need to spawn a new shell.

It is executed like this:

$ sudo command_to_executeUnlike su, the sudo command will request the password of the current user, not the root password.

Because of its security implications, sudo access is not granted to users by default. It must be set up before it functions correctly.

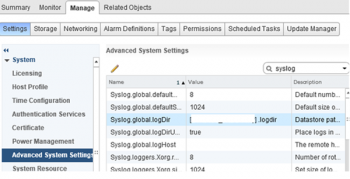

The sudo command is configured through a file located at /etc/sudoers.

You should not edit this file with a normal text editor.

Instead, use the visudo command.

The visudo command opens a text editor like normal, but it validates the syntax of the file upon saving. This prevents configuration errors from blocking sudo operations. It may be our way to obtain root privileges.

Traditionally, visudo opens the /etc/sudoers file with the vi text editor. Ubuntu, however, has configured visudo to use the nano text editor instead.

If we want to change it back to vi, we issue the following command:

$ sudo update-alternatives –config editorOutput

There are 4 choices for the alternative editor (providing /usr/bin/editor).

Selection Path Priority Status————————————————————* 0 /bin/nano 40 auto mode1 /bin/ed -100 manual mode2 /bin/nano 40 manual mode3 /usr/bin/vim.basic 30 manual mode4 /usr/bin/vim.tiny 10 manual mode

Press <enter> to keep the current choice[*], or type selection number:

Select the number that corresponds with the choice we would like to make.

On CentOS, we can change this value by adding the following line to ~/.bashrc:

$ export EDITOR=`which name_of_editor`Then source the file to implement the changes:

$ . ~/.bashrcAfter we configure visudo, execute the command to access the /etc/sudoers file:

$ sudo visudoHow to Edit Sudoers File in Linux ?

We will have the /etc/sudoers file in the text editor we choose.

Defaults env_resetDefaults mail_badpassDefaults secure_path=”/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/snap/bin”

root ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL

%admin ALL=(ALL) ALL%sudo ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL

#includedir /etc/sudoers.dMoving ahead, let’s take a look at what these lines do.

i. Default Lines

The first line, “Defaults env_reset”, resets the terminal environment to remove any user variables. This is a safety measure to clear potentially harmful environmental variables from the sudo session.

The second line, Defaults mail_badpass, tells the system to mail notices of bad sudo password attempts to the configured mailto user. By default, this is the root account.

The third line, which begins with “Defaults secure_path=…”, specifies the PATH for sudo operations. This prevents using user paths which may be harmful.

ii. User Privilege Lines

The fourth line, which dictates the root user’s sudo privileges, is different from the preceding lines.

Let us take a look at what the different fields mean:

root ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALLThe first field indicates the username that the rule will apply to (root).

root ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALLThe first “ALL” indicates that this rule applies to all hosts.

root ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALLThis “ALL” indicates that the root user can run commands as all users.

root ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALLThis “ALL” indicates that the root user can run commands as all groups.

root ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALLThe last “ALL” indicates these rules apply to all commands.

This means that our root user can run any command using sudo, as long as they provide their password.

ii. Group Privilege Lines

The next two lines are similar to the user privilege lines, but they specify sudo rules for groups.

Names beginning with % indicate group names.

Here, we see the admin group can execute any command as any user on any host. Similarly, the sudo group has the same privileges but can execute as any group as well.

iii. Included /etc/sudoers.d Line

The last line might look like a comment at first glance:

. . .#includedir /etc/sudoers.dHowever, this line indicates that files within the /etc/sudoers.d directory will source and apply.

Files within that directory follow the same rules as the /etc/sudoers file itself. Any file that does not end in ~ and that does not have a . in it will be read and appended to the sudo configuration.

As with the /etc/sudoers file, we should always edit files within the /etc/sudoers.d directory with visudo. The syntax for editing these files will be:

$ sudo visudo -f /etc/sudoers.d/file_to_edit

How To Give a User Sudo Privileges ?

The most common operation that users want to accomplish is to grant a new user general sudo access. This is useful if we want to give an account full administrative access to the system.

The easiest way of doing this on a system set up with a general-purpose administration group, like the Ubuntu system, is actually to add the user in question to that group.

For example, on Ubuntu 20.04, the sudo group has full admin privileges. We can grant a user these same privileges by adding them to the group like this:

$ sudo usermod -aG sudo usernameWe can also use the gpasswd command:

$ sudo gpasswd -a username sudoThese will both accomplish the same thing.

On CentOS, this is usually the wheel group instead of the sudo group:

$ sudo usermod -aG wheel usernameOr, use gpasswd:

$ sudo gpasswd -a username wheelOn CentOS, if adding the user to the group does not work immediately, we have to edit the /etc/sudoers file to uncomment the group name:

$ sudo visudo. . .%wheel ALL=(ALL) ALL. . .[Stuck with privileges Configuration in Linux? We'd be happy to assist]

How To Set Up Custom Rules in Linux ?

As we are familiar with the general syntax of the file, let us create some new rules.

How To Create Aliases ?

The sudoers file can organize more easily by grouping things with various kinds of “aliases”.

For instance, we can create three different groups of users, with overlapping membership:

. . .User_Alias GROUPONE = abby, brent, carlUser_Alias GROUPTWO = brent, doris, eric,User_Alias GROUPTHREE = doris, felicia, grant. . .Group names must start with a capital letter. We can then allow members of GROUPTWO to update the apt database by:

. . .GROUPTWO ALL = /usr/bin/apt-get update. . .If we do not specify a user/group to run as, as above, sudo defaults to the root user.

We can allow members of GROUPTHREE to shut down and reboot the machine by creating a “command alias” and using that in a rule for GROUPTHREE:

. . .Cmnd_Alias POWER = /sbin/shutdown, /sbin/halt, /sbin/reboot, /sbin/restartGROUPTHREE ALL = POWER. . .We create a command alias called POWER that contains commands to power off and reboot the machine. Then allow the members of GROUPTHREE to execute these commands.

Similarly, we can also create “Run as” aliases, which can replace the portion of the rule that specifies the user to execute:

. . .Runas_Alias WEB = www-data, apacheGROUPONE ALL = (WEB) ALL. . .This will allow anyone who is a member of GROUPONE to execute commands as the www-data user or the apache user.

The later rules will override the earlier rules when there is a conflict between the two.

How To Lock Down Rules in Linux?

There are a number of ways that we can achieve more control over how sudo reacts to a call.

The updatedb command in association with the mlocate package is relatively harmless on a single-user system. If we want to allow users to execute it with root privileges without having to type a password, we can make a rule like this:

. . .GROUPONE ALL = NOPASSWD: /usr/bin/updatedb. . .

NOPASSWD is a “tag” that means no password will be requested. It has a companion command called PASSWD, which is the default behavior.

A tag is relevant for the rest of the rule unless overruled by its “twin” tag later down the line.

For instance, we can have a line like this:

. . .GROUPTWO ALL = NOPASSWD: /usr/bin/updatedb, PASSWD: /bin/kill. . .Another helpful tag is NOEXEC, which can be used to prevent some dangerous behavior in certain programs.

For example, some programs, like less, can spawn other commands by typing this from within their interface:

!command_to_runThis basically executes any command the user gives it with the same permissions that less is running under, which can be quite dangerous.

To restrict this, we could use a line like this:

. . .username ALL = NOEXEC: /usr/bin/less. . .Additional Information relating to using SUDO?

There are a few more points that may be useful when dealing with sudo.

If we specify a user or group to “run as” in the configuration file, we can execute commands as those users by using the -u and -g flags, respectively:

$ sudo -u run_as_user command$ sudo -g run_as_group commandFor convenience, by default, sudo will save the authentication details for a certain amount of time in one terminal.

For security purposes, if we wish to clear this timer, we can run:

$ sudo -kIf, on the other hand, we want to “prime” the sudo command, not to prompt later, or to renew the sudo lease, we can always type:

$ sudo -vWe will be prompted for the password, which will be cached for later sudo uses until the sudo time frame expires.

If we need to know the privileges, we can type:

$ sudo -lThis will list all of the rules in the /etc/sudoers file that applies to the user.

There are many times when we will execute a command and it will fail because we forgot to preface it with sudo. To avoid having to re-type the command, we can take advantage of a bash functionality that means “repeat last command”:

$ sudo !!The double exclamation point will repeat the last command. We preceded it with sudo to quickly change the unprivileged command to a privileged command.

We can add the following line to the /etc/sudoers file with visudo:

$ sudo visudo. . .Defaults insults. . .This will cause sudo to return a silly insult when a user types in an incorrect password for sudo.

Output:

[sudo] password for demo: # enter an incorrect password here to see the resultsYour mind just hasn’t been the same since the electro-shock, has it?[sudo] password for demo:

My mind is going. I can feel it.[Need further assistance with Linux related Installations? We are available 24*7. ]

Conclusion

This article will guide you on how to edit #Sudoers File in Linux which involves #root privileges, with a special focus on editing the /etc/sudoers file. You can configure who can use #sudo #commands by editing the /etc/sudoers file, or by adding configuration to the /etc/sudoers. To edit the sudoers file, we should always use the #visudo command. This uses your default editor to edit the sudoers configuration.

This article will guide you on how to edit #Sudoers File in Linux which involves #root privileges, with a special focus on editing the /etc/sudoers file. You can configure who can use #sudo #commands by editing the /etc/sudoers file, or by adding configuration to the /etc/sudoers. To edit the sudoers file, we should always use the #visudo command. This uses your default editor to edit the sudoers configuration.